As Seattle and the region grapple with increasing homelessness, basically everyone agrees the national heroin epidemic is contributing to the crisis.

In 2014, King County saw 156 heroin-related deaths, the highest in 20 years, according to the county. Meanwhile, as of last October, the county says more than 150 people were on the waitlist for methadone treatment each day, on top of the 3,615 people in the county who were receiving the treatment.

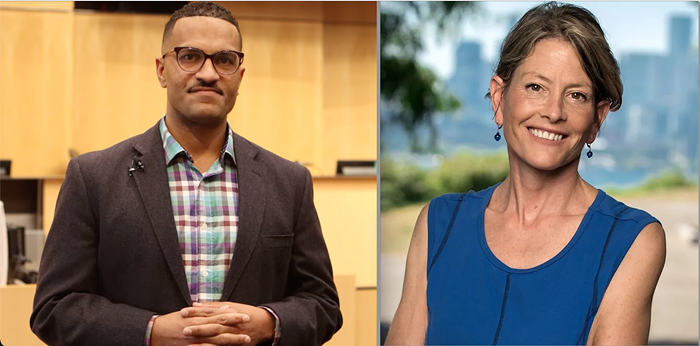

Yesterday, King County Executive Dow Constantine and Seattle Mayor Ed Murray announced a task force made of local law enforcement officers, medical professionals, and social service providers to tackle the growing heroin and opiate addiction epidemic in the region.

“I have declared a state of emergency to address homelessness, but I am told by our outreach workers and officers that hundreds of the people who live on our streets are struggling with addiction,” Murray said in a statement. “If we are ever to get people into permanent housing, we must do more on chemical dependency treatment."

Officials say the task force will begin meeting this month to look for short- and long-term ways to:

• Expand treatment capacity

• Increase access to evidence-based treatment options

• Expand prevention efforts

• Increase public awareness and understanding of addiction

• Explore other options and opportunities to improve access to treatment on demand and reduce overdose and death.

(The full list of task force members, some still TBD, is here.)

“Addiction to heroin and prescription pain killers is devastating families in every one of our communities—sparing no age, race, gender, neighborhood or income level,” Constantine said.

While treatment will likely be the focus of the task force, immediately reducing harm should also be on the table. Vancouver, B.C. has a safe injection site and advocates want American cities to follow. A movement for safe-consumption sites is building in Seattle. A coalition is pushing for them in New York City and a mayoral task force in San Francisco has recommended them. Healthcare workers in Boston, meanwhile, are planning a "safe space," where people won't be able to use drugs but can go if they're high.

From the Marshall Project (emphasis mine):

“A lot of people are homeless or unstably housed, and when people are injecting in public it tends to be riskier,” says Daniel Raymond, Policy Director at the New York City–based Harm Reduction Coalition. “They tend to rush because they don’t want to be seen. This increases risk for overdose, for spreading infections. There’s logic to saying, if you’re at risk of overdose, let’s at least be inside where someone can respond.”

Many years of research have shown that supervised injection facilities reduce overdose deaths, prevent the spread of HIV and hep C, increase the likelihood that users will seek drug treatment or other medical care, and decrease street crime and discarded syringes in public areas.

To make the safe consumption site model work in Seattle, advocates will need buy-in from city officials and especially law enforcement. This task force could be an important step in that direction.