Psych, metal, and folk producer Randall Dunn is a locksmith of sound. He interprets sonic combinations. He's also a songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and animal-necromancer in Seattle's own Master Musicians of Bukkake. He plays a double-reed zurna while reading minds. There's an unwavering resolution about Dunn. He's a psych and drone theorist with extremely tuned ears, and he has knowledge of the way frequencies in a mix meld and work. For MMOB, he tends to enter through the portal of extended, Eastern-bent drones. Dunn simultaneously appreciates chaos and serenity. He applies a meticulous, measured approach to his productions, while leaving room for human roaming in the margins. Besides his own MMOB releases, his production credits range from Wolves in the Throne Room and Sunn O))) to Midday Veil, Marissa Nadler, and Australian minimal guitarist Oren Ambarchi. MMOB have a release titled Further West due out in January. I met Dunn in the Caffe Vita Bean Room. He was on his way to Avast! Recording Co. to work with Eyvind Kang.

What are you working on with Eyvind today?

Some music that will be part of a release that Alan Bishop is putting out on Abduction. Not sure when it's coming out. Eyvind does stuff until it's the way Eyvind wants it to be, then it's finished. We did an album years ago called Live Low to the Earth in the Iron Age that was [also on Abduction]. This is sort of his follow-up to that.

What brought you to Seattle from Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1993?

I originally was going to go to school for sound design at the Art Institute of Seattle, to learn audio for film. My original goal was an interdisciplinary thing of video and film. I'm sort of a frustrated filmmaker that turned into a record producer. The people I met when I moved here spun me in way that sent me down this path of treating sound the way I would have treated film.

When did you first marry yourself to sound?

I got a little Casio keyboard for Christmas when I was 10 or 11. It had these 8-bit songs you could play along with. I was infatuated with it. I'd plug it into a cassette player and record it being really distorted. That was the first time I realized I was engaging with sound and music, and wasn't aware yet how to apply it. I guess the first time I consciously thought, "I want to do this," would have been Pink Floyd's The Wall? I was 13, it was another Christmas. I asked for it. [Laughs] The production sank in, that sound of a more theatrical rock-and-roll situation. The conceptual narrative. Then I found Dark Side of the Moon. Once you find those records, it's sort of a gateway drug.

The Casio's samba beat spoke to you.

For sure. The rock and disco beats were good, too. It had a "sample" function. I remember running around the house recording things on it. It's an SK-1. I still have one, and it still appears on albums that I do.

How will you go about sculpting Eyvind's sound?

With him, it's always very specific. We've been collaborating on recordings for almost 20 years. We don't even talk about it any more. He's such a gifted composer. It's more like I'm trying to translate or understand what he's giving me and give it a context sonically, or prompt an overdub. There's a high level of trust between us, and we bounce things back and forth pretty rapidly. He's so intuitive; I've learned a lot from him. He was my very first session ever, and hopefully he'll be my last.

You morph your ears aptly per each project, as part psychologist and scientist. Let's take Leigh Stone's new Modern Ruins album you produced. It sounds great—a goth, rock, Thompson Twins, Kate Bush, PJ Harvey thing.

I think when there's a pop element, vocal and rhythm are important there. With Modern Ruins, there was room to play a role in the music. I think I contributed to it with my influences. Working within the context of songs is different than sculpting open-ended movements. Leigh is great. For them, I really tried to alter and tailor synthesizer sounds, using filters and processing to give unique hue. I feel like there's not much digital deviation on a lot of records these days. I want to shade things differently. Avast! is a great place to do things. It's a perfect storm there, a fluid workspace. It's meticulously maintained. The staff is tops. They've curated it with the right gear. It's comfortable. I've developed a great relationship with Stuart Hallerman, who owns it. The API board there was made for Lenny Kravitz in the '90s.

Do the ghosts of Lenny Kravitz speak to you through the channels?

Occasionally. Sometimes if you put a guitar through it, it has a sound. Possibly Kravitz. It sounds just like his character in the Hunger Games movies. He's like the helper guy. [Laughs] I'm not a huge fan of the predictability of digitally processed music. But when you combine it with analog, you can get a cool medium. I rarely mix in the box, or use Pro Tools to do mixes. Everything is hands-on with faders. I'll start with tape—if it's a rock band, recording to 16-track two-inch tape. It's a beautiful sound you don't hear much of any more. I like the hybrid approach with the soul of tape and the precision of digital.

Why does tape sound richer? How do you describe the depth tape gives, or that soul?

The technical reason is that there are no limitations to the fidelity of tape other than the frequency response of the tape machine. It's not a sample-based recording format. Digital cuts your signal up into bits and kilohertz with limits. You don't get a continuous waveform when you're recording with Pro Tools. Tape has no cuts when transduced. It may be imperceptible, but perhaps that's why it sounds rich the way it does. It's also a bit like film versus digital. Tape, like film, is more superstitious. It's an electromagnetic thing. Some people say the soul is electromagnetic; maybe there's a relationship there. When you're dealing with tape, maybe it's the way people relate to music without a screen. Tape is more tactile. Plus, there's the precedent of every record we love prior to 1999 being on tape.

What's the most perfect sound you've ever heard?

Perfect sounds, I don't know. I like imperfect sounds. In Istanbul, Turkey, there's a cistern that was built in like the year 570. It's down these steps in the Sultanahmet district. If you didn't know it was there, you'd miss it. I'll go down there and sit. The sound of the water reverberating is extremely compelling. There's a door with the year on it, and two heads of Medusa inside. One is upside down. I think the Byzantine Empire put them there as symbols of dominance over the old gods, or maybe the opposite—some kind of reimagining. There are hundreds of carp there, these eerie fish swimming around that you can barely see. It's dank and dark. When you're in there, you're just kind of fathoming how old it is. It's old. A church is above it. I've always wanted to record there.

How do you gain the objectivity to produce your own band?

I trust the people in that band implicitly—their ears, and their opinions. [MMOB drummer] Dave Abramson is really gifted with sounds. We've cultivated a solid chemistry. When I'm mixing, it tends to help if I disassociate from the band somewhat. That enables me to hear things objectively and know what's working. Otherwise, I'd never be able to finish mixing. I'd be tweaking it for eternity. [Laughs] I try to encourage and allow for spontaneity and imperfections. We wrote most of our last album in the studio. Make no mistake, though, it's not roses all the time. I can be a jerk in the studio.

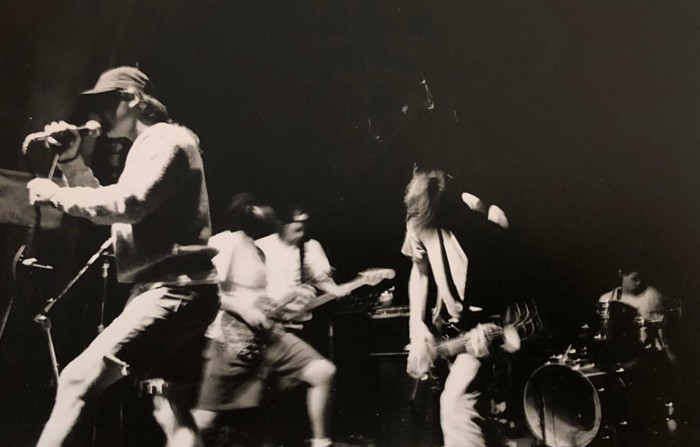

I saw you all play at the Funhouse once. You played one song for 45 minutes.

That can happen. In between albums, I like to let sets lean on the mysterious outside forces. For that show, everyone was on guitar, we decided on a key signature, and everyone needed to bring a part to offer. I think it makes you pay attention to what you're playing in a different way. For Hypnotikon, we'll be doing an all-guitar set with a little bit of synth. It's a piece that Don McGreevy wrote based on the modal aspects of Raga Malkauns.

Define raga.

A traditional form of Indian music that has an ascension and a descension, and is relative to a tonic or a drone note. I have such respect for Indian classical musicians.

When Master Musicians of Bukkake perform live, you all take on altered forms. You're draped in robes; your faces are hidden. Brad Mowen stands behind an altar of sorts made of effects for his vocals. He's this genderless being. There are antlers. Is that an animal god?

Watching that guy onstage 30 nights in a row on tour is gratifying. He's as dedicated as you can be. It's a shamanistic thing for him. I don't know if that's animal-god territory. With a lot of psychedelic music, and I don't know if I put us in that category, there's a faux-ritual aspect that bands like to play up. There are costumes that accentuate that—the mysticism or tribalism. We've never been a part of that. We use costumes in a much more oblique manner. It's very much not occult. It's more about being onstage as an entity, using those costumes to unify us. The costumes have shifted recently. Now we resemble UN soldiers. It's the final chapter of a narrative that started with our first record. There will be some sort of disaster-relief action happening at the Triple Door show.

I thought your song "Prophecy of the White Camel" was "Prophecy of the White Caramel" for the longest time.

That would be good. Like a mocha? A coffee drink in Seattle that's been talked about, but not made yet. [Laughs] The Prophecy of the White Camel is an ancient Bedouin creation myth. That's my breakup song, actually. The only breakup song I've ever written. The lyrics happened using a Bedouin phrase dictionary. The sentiment is about suffering and learning about yourself going through it.

So you're not an animal god in a trance onstage?

I don't want to ruin anything for you. I try to be very present onstage. Lots of psychedelic bands try to escape, but with our costumes and music, we want to do the opposite. I want it to be awakening, confrontational, and tantric. A spectacle that wakes you, rather than puts you to sleep in a drug-addled haze. It's a state. I'm always in a trance. If I've had a lot of coffee, I'm almost in a trance.

When you're 39 minutes into a song, where does your brain go?

I've definitely left a few times. I play a double-reed instrument from Turkey called a zurna. I almost passed out one time. You have to use circular breathing. Playing that for a prolonged amount of time can put you in a trancelike state. We did a show once, and the singer from the Norwegian black-metal band Gorgoroth named Gaahl was in the crowd. He's legendary. I was playing a long Tibetan instrument called a dung-chen to open the show. It was really loud through the PA. It takes a lot of air to play it; you can get light-headed. I looked up and saw Gaahl out in this crowd of about a thousand people. It looked like he had a spotlight on him. He was stroking his beard, looking at me, and we made eye contact, and he raised his hand with this dark approval. It can be hard to reintegrate after a show. Especially for Brad. He'll make up languages. But we have to integrate quickly, because we have to go to the merch table.

For me, MMOB is animalistic. Have you ever seen cobras mate?

Not in person, but I know they twist when they mate, and it looks like a DNA helix.

If you could mate any two things, what would they be?

Perception and consciousness. That would be cool. I think it would also be great to see how big an animal there could be. So, a blue whale and an elephant? A blelephant? Which would be rad. I think we need more imposing animals on the earth. ![]()